Tuesday, February 27, 2024

7:00 PM — 9:00 PM

Cordiner Hall (map)

Google Calendar | ICS

Not sure what to wear? Where to park? When to clap? Check out our Concert Guide!

Timothy Chooi is represented by Colbert Artists Management, Inc.

“Embark on an extraordinary musical journey with the Walla Walla Symphony as we present “Rising Stars: An Exploration of Innovation” and Classics.” Be captivated by the exceptional talent of rising star violinist Timothy Chooi in Sibelius’ Violin Concerto, discover the modern brilliance of Jessie Montgomery’s Starburst and immerse yourself in the timeless beauty of Brahms’ Symphony No. 3, as conductor Dina Gilbert brings together emerging talents and enduring compositions in a captivating symphonic experience. Join us for an unforgettable evening celebrating rising stars of classical music.”

– Dina Gilbert

Jessie Montgomery - Starburst

Jean Sibelius - Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47

Timothy Chooi, violin

Johannes Brahms - Symphony No. 3 in F major, Op. 90

Timothy Chooi's appearance is made possible by the WW Symphony Guest Composer/Artist Fund - Underrepresented Voices

Dina Gilbert's appearance is made possible by the Katherine and Walter Weingart Guest Artist Endowment

WINE SPONSOR

Wine from our wine sponsor will be available before the concert and during intermission for $5/glass (all proceeds benefit the Walla Walla Symphony).

About the Guest Artist

Timothy Chooi, violin

Powerful and finely nuanced interpretations, sumptuous sonorities, and a compelling stage presence are just a few of the hallmarks of internationally acclaimed violinist, Timothy Chooi. A popular soloist, recitalist, and chamber musician, he is sought after for his wide-ranging and creative repertoire. Recent honors include 2nd Prize at the most prestigious violin competition in the world, Queen Elisabeth Competition, 1st prize at the Joseph Joachim International Violin Competition in Germany, and Switzerland’s coveted Verbier Festival Paternot Prize.

His recent engagements on the world stage include his debut at the Berlin Philharmonie, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, European tours with the Wiener Concert-Verein, Amsterdam's Royal Concertgebouw, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and collaboration with Anne-Sophie Mutter at Vienna’s Musikverein, and Paris’ Theatre Champs-Elysses to name a few.

With his wide-ranging international experience, Chooi is passionate about developing violin pedagogy and is the Professor of Violin at the University of Ottawa. He currently performs on the 1741 "Titan" Guarneri Del Gesu violin on loan from Québec's CANIMEX and the 1709 "Engleman" Stradivarius from the Nippon Music Foundation in Japan.

Program Notes

© John David Earnest, 2024

Jessie Montgomery

Starburst

Date of Composition: 2012

Last WWS performance: First performance at this concert

Approximate length: 8 minutes

© Jiyang Chen

Jessie Montgomery is an acclaimed composer, violinist, and educator. She is the recipient of the Leonard Bernstein Award from the ASCAP Foundation, the Sphinx Medal of Excellence, and her works are performed frequently around the world by leading musicians and ensembles. Her music interweaves classical music with elements of vernacular music, improvisation, poetry, and social consciousness, making her an acute interpreter of 21st century American sound and experience. Her profoundly felt works have been described as “turbulent, wildly colorful and exploding with life” (The Washington Post).

Her growing body of work includes solo, chamber, vocal, and orchestral works. Some recent highlights include Shift, Change, Turn (2019) commissioned by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Coincident Dances (2018) for the Chicago Sinfonietta, and Banner (2014)—written to mark the 200th anniversary of “The Star-Spangled Banner”—for The Sphinx Organization and the Joyce Foundation, which was presented in its UK premiere at the BBC Proms in 2021.

Since 1999, Jessie has been affiliated with The Sphinx Organization, which supports young African American and Latinx string players and has served as composer-in-residence for the Sphinx Virtuosi, the Organization’s flagship professional touring ensemble. A founding member of PUBLIQuartet and a former member of the Catalyst Quartet, Jessie holds degrees from the Juilliard School and New York University and is currently a PhD Candidate in Music Composition at Princeton University. She is Professor of violin and composition at The New School. In May 2021, she began her three-year appointment as the Mead Composer-in-Residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The composer has written the following program note for Starburst:

“This brief one-movement work for string orchestra is a play on imagery of rapidly changing musical colors. Exploding gestures are juxtaposed with gentle fleeting melodies in an attempt to create a multidimensional soundscape. A common definition of a starburst (‘the rapid formation of large numbers of new stars in a galaxy at a rate high enough to alter the structure of the galaxy significantly’) lends itself almost literally to the nature of the performing ensemble who premieres the work, The Sphinx Virtuosi, and I wrote the piece with their dynamic in mind.”

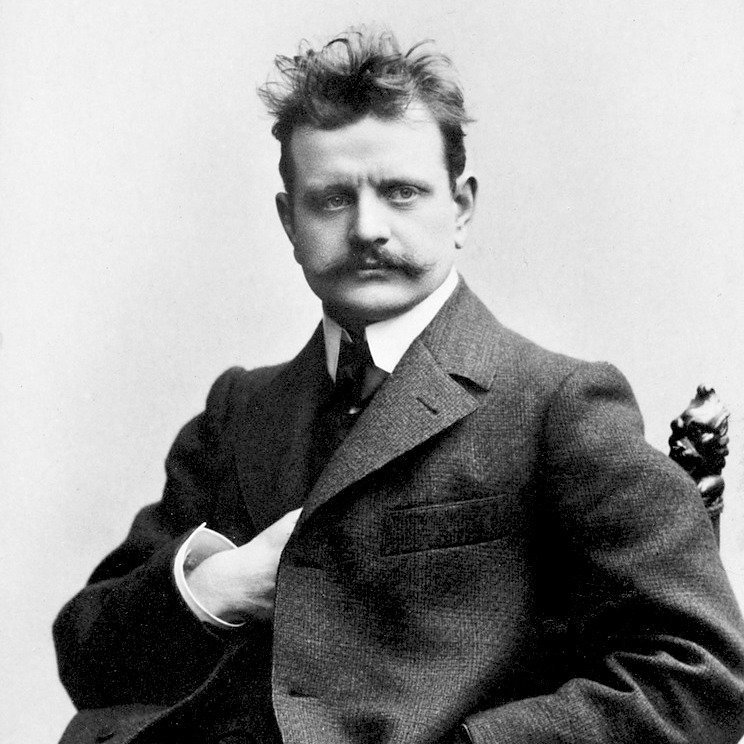

Jean Sibelius

Violin Concerto in D Minor, Op. 47

Date of Composition: 1905

Last WWS performance: October 22, 2002

Approximate length: 35 minutes

One of the most unique musical figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the great Finnish composer, Jean Sibelius, generated profound adulation from his admirers and remains a vastly popular symphonist. His well-known work, Finlandia (1899-1900), has long been a staple of the symphonic repertory; it was written as a protest to the Russian oppression of Finland. Sibelius was solidly in the tradition of 19th century nationalist composers; he sought to define a national identity for Finland through his music. Listening to Sibelius can be a fascinating and transforming experience. His musical ideas take vast amounts of time to unfold, but the eventual culmination is always overpowering and deeply gratifying. The listener need only settle into the glacial splendor of these large-scale structures to appreciate the musical glories found there.

Sibelius wrote only one concerto, the Violin Concerto in D Minor. The composition of the work was the composer’s fulfillment of a youthful dream of becoming a violinist himself. He studied the violin and became accomplished enough to play in the Vienna Conservatory’s orchestra when he was a student there, in 1890–91, but his stage fright and lack of technical skills ended that ambition. He began work on the concerto in 1902, finishing it in 1904. After a disappointing premiere performance by an incapable soloist, Sibelius revised the piece, completing it in 1905. The new version was successfully performed by the concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Richard Strauss. It was not until 1935, however, when Jascha Heifetz recorded the concerto, that the piece finally gained a place in the concerto literature.

Over a barely audible whisper of murmuring strings, the solo violin introduces the principal theme of the first movement, a darkly moody sigh that gradually stirs to life. It’s a musical utterance of both longing and passion, one that will appear many times throughout the movement. The composer’s compositional hallmarks are evident everywhere: somber orchestra colors, swelling brass chords, slow harmonic movement, and poignant melodic ideas. The most unusual feature of the movement is the role of the violin in the movement’s overall structure. The cadenza, an extended virtuosic passage played only by the soloist and traditionally placed near the end of the movement, is now positioned by Sibelius in the middle of the movement, emotionally anchoring the central section before moving forward. The movement ends with a dazzling passage of octaves played in rapid succession by the soloist, leading to a dramatic finish.

The second movement opens with pairs of woodwinds playing a wistfully simple tune. The violin follows with a melancholy melody that is one of the composer’s finest. But the orchestra responds not with tenderness, but with mounting intensity. After a brooding climax by both soloist and orchestra, the movement gradually subsides as the violin vanishes on a quiet, high note.

The final movement is a feast of violin virtuosity, one of the most demanding in the repertoire. The heavily driving rhythm of the theme is a foot-pounding dance and has been called by Donald Tovey, a renowned musicologist, “…a polonaise for polar bears.” The soloist and orchestra intensify the rhythm as the dance tune continues, plunging toward a spectacular finish.

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90

Date of Composition: 1883

Last WWS performance: May 20, 2014

Approximate length: 40 minutes

The four symphonies of Brahms are anchored in the orchestral literature like giant pillars supporting the imposing edifice of 19th century symphonic composition, a craft mastered by the disciplined genius of this great German composer. His colleagues expected that his first symphony would be heir to the symphonic legacy of Beethoven, an expectation that weighed heavily on Brahms. Thus, it wasn’t until Brahms was over 40 years old that he would finally complete his first symphony, the renowned C Minor, Op. 68, in 1876. The second symphony, in D Major, Op. 73, followed in 1877. Then a period of intense productivity saw the composition of the second piano concerto and the violin concerto, as well as many songs and piano pieces. The third symphony, in F Major, Op.90, the shortest of the four, was premiered in 1883 by the Vienna Philharmonic, conducted by Hans Richter, and finally, the monumental fourth symphony, in E Minor, Op. 98, in 1885.

Brahms’ close friend, the famous violinist Joseph Joachim, had adopted a personal motto: Frei aber einsam (free, but lonely). Brahms took a similar motto, but with an important twist: Frei aber froh (free, but happy). The three initial letters of the motto (F-A-F and F-A flat-F) are the opening notes of Symphony No.3. This three-note motive functions as both thematic and harmonic material throughout the first movement. There are other musical references in the movement: a brief phrase similar to a passage in Schumann’s Rhenish Symphony; an allusion to a harmonic progression in the Siren’s Chorus from Wagner’s Tannhäuser; and a melodic fragment from Liszt’s song, Die Loreley (another siren).

It’s important to note that the fabled rivalry between Brahms and Wagner was not between the composers themselves, but rather, between their respective disciples. Hugo Wolf, an ardent supporter of Wagner, disdained the music of Brahms, whereas Eduard Hanslick, the powerful Viennese music critic, sharply attacked Wagner’s music. The personally reticent Brahms would not participate in such pettiness; in fact, he admired Wagner’s work.

Following the intricacies of the opening movement, the second movement introduces a characteristically simple Brahmsian melody, one that suggests a folk song sung in an alpine setting. The melody is written for a favorite instrument of the composer, the clarinet. But the innocence of this lovely tune is followed by a series of unsettling chromatic chords and a rhythmically vigorous section that leads to a quiet end to the movement.

The most memorable movement of this symphony is the third, the Andante with its poignantly enchanting waltz tune, one of Brahms’ most famous melodies. He was fond of Central European folk music, especially music that in the 19th century was associated with Hungary; but this darkly supple melody is influenced not by the music of Hungarian peasants, but by Romani music. Brahms often used the phrase Alla Zingarese to indicate a musical style based on Romani music.

The final movement of the symphony opens with a rapidly surging theme that unfolds in a forceful declamation of dramatic orchestral bursts. Intricate rhythmic patterns create a sense of displacement and imbalance. But following all this storminess, the movement subsides into a quietly thoughtful chorale which gradually relaxes the entire structure of the symphony and brings it to a quiet conclusion with a gentle reprise of the opening motto of the work.